hawai‘i triennial 2022

@ BISHOP MUSEUM

@ HAWAI‘I STATE ART MUSEUM

@ HONOLULU MUSEUM OF ART

@ ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER

@ UNEXPECTED ENCOUNTERS

Lawrence Seward

b. 1966, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu

lives and works in Kuliʻouʻou, Kona, Oʻahu

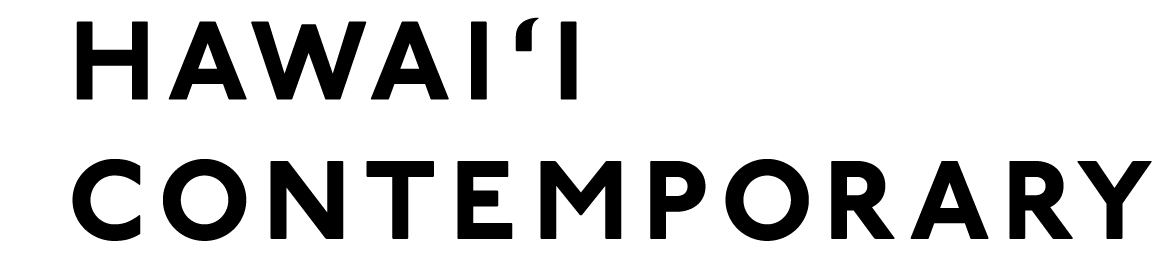

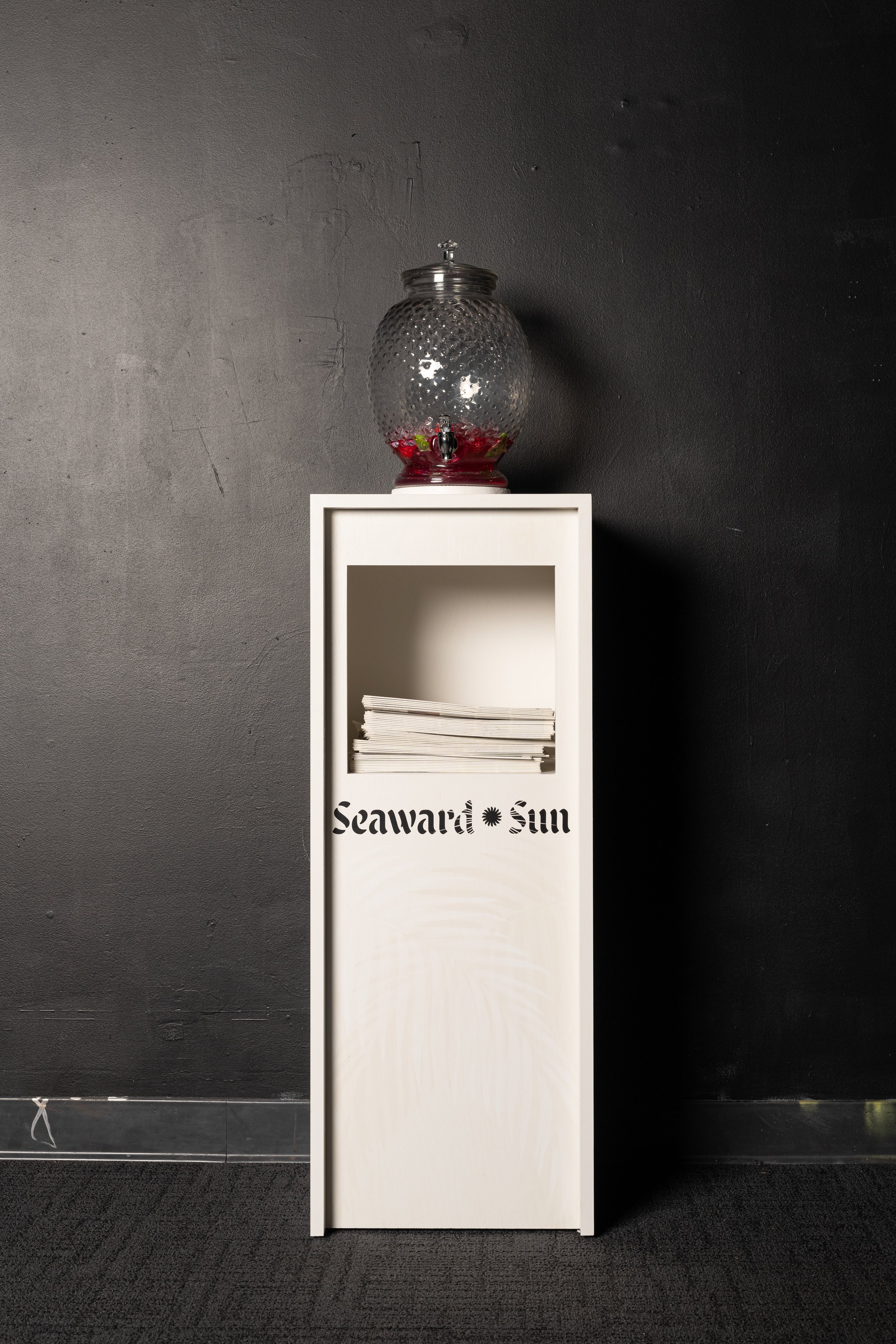

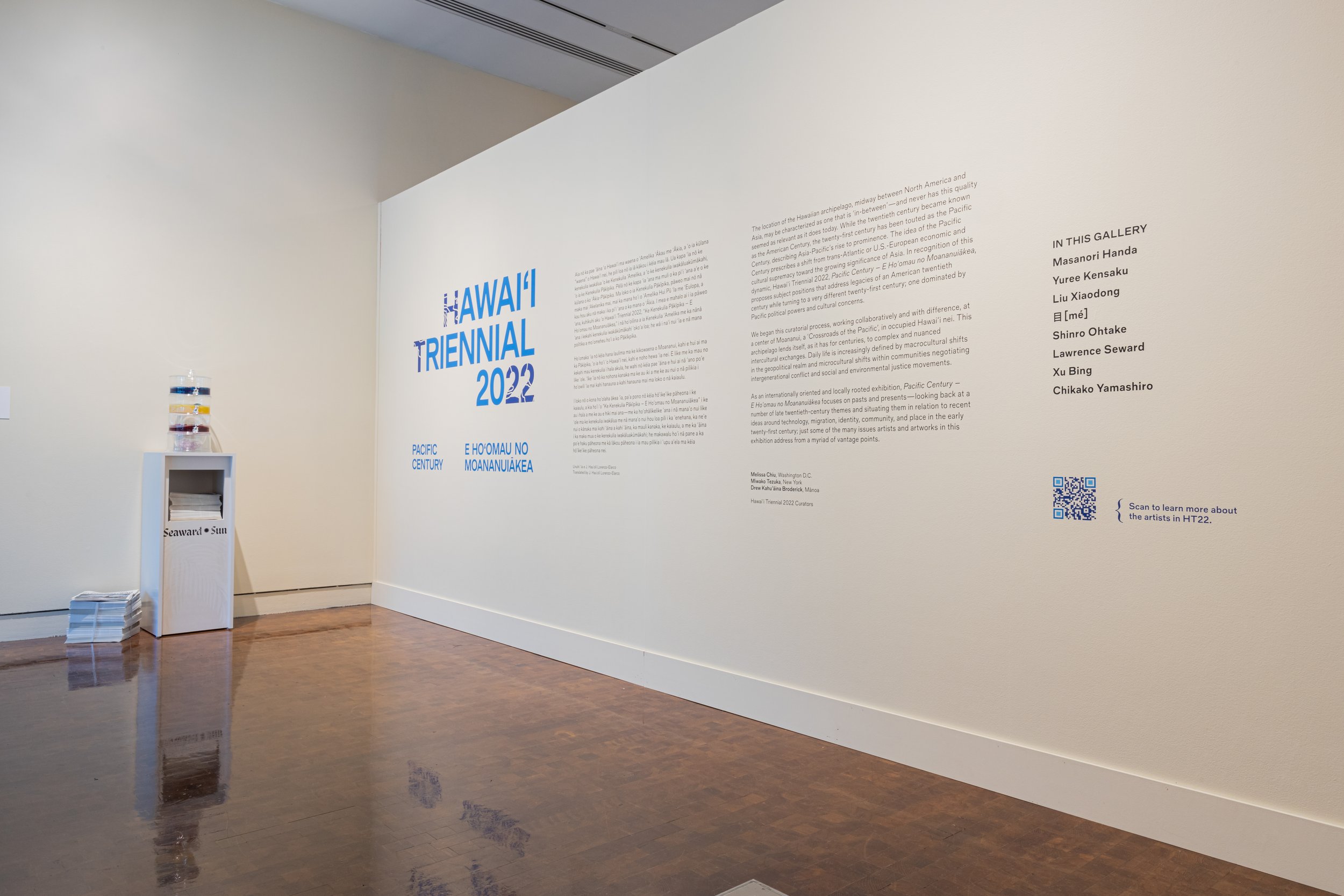

Installation views: Lawrence Seward, Seward Sun, 2021, Hawai‘i State Art Museum, Bishop Museum, Royal Hawaiian Center, and Honolulu Museum of Art, HT22, Honolulu. Courtesy of the artist and Hawai‘i Contemporary. Photos: Christopher Rohrer and Lila Lee.

Lawrence Seward has been making, handling, advocating for, and periodically organizing exhibitions of local, national, and international art since the rise of ‘multiculturalism’ in the 1990s. Seward engages with glocal discourses self-consciously (and at times reluctantly) from a position imbued with nostalgia and hope. Casual yet calculated, his understated work—whether it takes the form of drawings, paintings, publications, sculptures, videos, or installations—frequently deploys tropical kitsch aesthetics to interrogate notions of ‘Paradise’. Seward’s recent work focuses on current and longstanding issues related to popular culture, mis/re/appropriation, tourism, environmental catastrophe, and loss of the ‘real’.

As part of his 2014 exhibition titled End of the Rainbow, staged at now-defunct SPF Projects in Kakaʻako, Oʻahu, Seward presented a cluster of hinged wooden reef-fish maquetes—menpachi, porcupine, humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa, Moorish idol, uhu—mounted on large chunks of bleached coral carved from polystyrene. Produced in collaboration with Ghanaian fantasy-coffin artist Paa Joe, each fish was filled with Mary Jane molasses candies: treats for visitors and a bitter-sweet reminder of a September 2013 molasses spill that devastated marine life in Honolulu Harbor. A series of paintings depicting ‘paper lei’—offerings to the dead—floating in a sugary slick sea completed the scene. In another room, photographs of beach sculptures made from debris collected along the shoreline of Maunalua Bay accompanied a wooden-mask water feature shedding endless hysterical tears for the condition of the planet.

A few years later, in 2019, Seward collaborated on Rainbow Hash at Aupuni Space in Kakaʻako. A large plinth painted electric blue filled the gallery. Scattered across its surface were cast concrete rocks, and wedged into each one was a postcard collage from a series of mail art. Circulated at irregular intervals over the course of 2018, back and forth between Hawaiʻi and New York, no one went on vacation. Instead, Seward and his correspondent wrote on, cut-up, burned, sanded, scratched, stickered, taped, glued, tattooed, and sent cards as day-to-day schedules permitted—before work, after school, during lunch break, ‘whenev’ahs’. As many have noted, outmoded media, in this case postcards and mail art, often become their own form of generative potential. Fantasies of Hawaiʻi as an island getaway swirled with references to the ‘Western art’ of continental urban epicenters. The mythos of each place was read with and against the other. A sarcastic line from one of the fictional letters opines, ‘It’s so nice here! I can sit back and forget about all the problems facing the world.’

For HT22 Seward continues to explore the desire to escape, this time through a free tabloid newspaper available at custom vending machines across select HT22 locations and community venues. Composed of sensational articles and images sourced from family and friends, the tabloid includes a lead story written in collaboration with editor Lesa Griffith chronicling the downfall of New Dawn Island (NDI), an imagined man-made tropical resort and residence. Describing the cult-like scene, Seward says:

Triggered by an evolving pandemic in the outside world, which eventually finds its way into NDI’s regulated system, incoming supplies are limited and around eight thousand people are caught, isolated on a collapsing island paradise. Food, social services, and healthcare are pushed to the brink, provisions are at an all-time low, electricity is inconsistent as the only reliable sources of energy, solar and wind, are inadequate to meet the demands. Drinkable water is scarce and extremely valuable... Eventually, almost everyone dies in a mass murder-suicide inflicted by the island’s creator, who poisons everyone in his final act.

Lawrence Seward, New Dawn Island, 2021, digital rendering. Courtesy of the artist. © Lawrence Seward.

Image from Seward Sun, 2022, newspaper and mixed media, 20 pages, edition of 5,000. Courtesy of the artist.

Lawrence Seward born and raised in Hawai’i, has shown his artworks internationally but mainly in New York City where he lived for seventeen years.has been making and showing art professionally since 1990. He was represented by and exhibited at the Andrew Kreps Gallery (New York City) for 13 years. His international exhibitions include MOMA/PS1, the Aldrich Museum, Gallery Edward Mitterand, Richard Heller Gallery. Seward is in the collections of Dikeou, Emily Fischer Landau, the Whitney Museum of American Art, Dakis Joannou, and the Honolulu Museum of Art. His work has been reviewed by the New York Times, The New Yorker, Dwell Magazine, Frieze magazine, and the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Seward is currently living and working in Honolulu but is very interested in drawing attention to the contemporary art scene in Hawaii. Prior to teaching at the University of Hawaii he has taught at the Pace University and is co-owner of an art related business All Art LLC. He was recently in a four person exhibition in Honolulu with Ashley Bickerton, Paul Pfeiffer and Garnett Puitt.