hawai‘i triennial 2022

@ BISHOP MUSEUM

Karrabing Film Collective

Lives and works in the Belyuen Community,

the Northern Territory, Australia

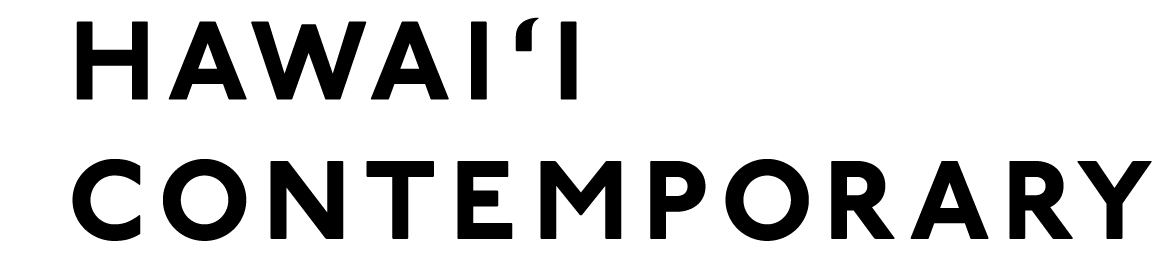

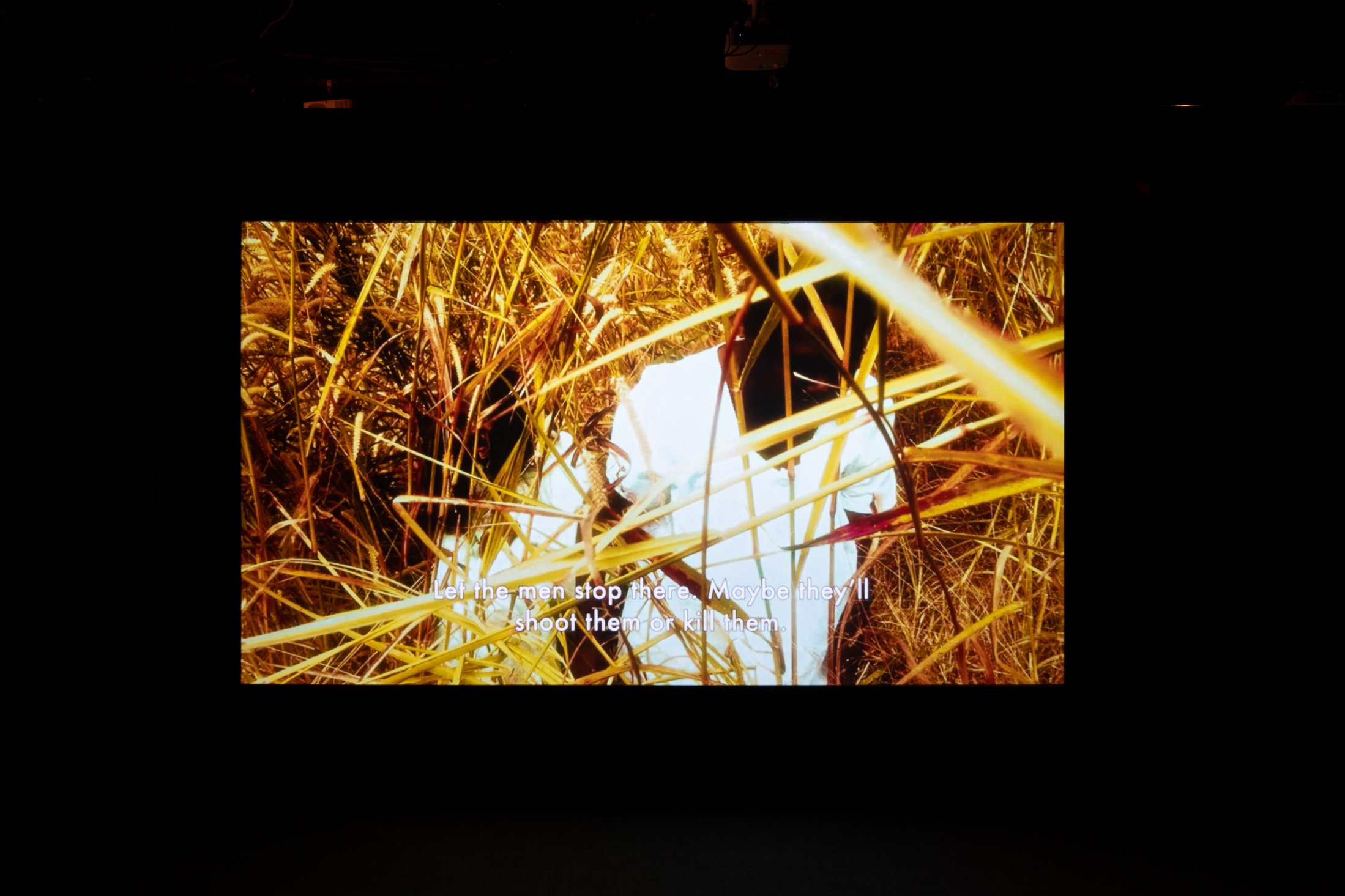

Installation views: Karrabing Film Collective at Bishop Museum, HT22, Honolulu. Courtesy of the artists and Hawai‘i Contemporary. Photos: Christopher Rohrer.

Initiated in 2008 in the Northern Territory, Australia, Karrabing Film Collective consists of more than thirty intergenerational members of an extended family whose ancestral places stretch across warm saltwater coastlands of Australia to the frozen freshwaters of the Italian Alps. Their collective name, sourced from ‘karrabing’, a word of the Emmiyengal Indigenous language group of Northern Australia, refers to a time when the regional tides are at their lowest—a moment in the ebb and flow of the ocean that facilitates collective gatherings in the Belyuen community, where most of the Karrabing’s members reside, and in their southern coastal lands.

As an expression of Indigenous grassroots activism in art, the collective approaches film and installation-making as a mode of self-organization—beyond government-imposed structures of clanship or land ownership—and a means of interrogating the legacies of settler colonialism and the ongoing social conditions of inequality that define their ways of being and homeland today. Throughout their many short films, which center on animate and inanimate life in more-than-human worlds, the collective deploys improvisational realism to clear a space outside of the binaries of fiction and documentary, past and present.

Karrabing activates the potential of collaborative community storytelling to subvert the violence of longstanding and ongoing dispossession, conversion, surveillance, extraction, and devastation that characterize existence in ‘late toxic liberalism’— a term put forth by Elizabeth A. Povinelli, one of the collective’s founding members, and an anthropologist and gender studies professor who has worked closely as an accomplice alongside the community since 1984. Shot on handheld cameras and phones by a rotating cast, the collective has stated that many of their films ‘dramatize and satirize the daily scenarios and obstacles that members face in various interactions with corporate and state entities.’

Their film Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (2018), for example, tells the story of a young Indigenous man, played by Aiden Sing, taken as a baby to be part of a medical experiment to save the white race in a not-so-distant future where Europeans can no longer survive outdoors in a world poisoned by settler-colonial capitalism. An earlier work, The Jealous One (2017), offers a new take of an old story: an Indigenous man, played by Rex Edmunds, navigates through bureaucratic red tape to get to a mortuary service in his traditional country, while another man, played by Trevor Bianamu, is consumed with jealousy. The film opens with an unsettling phone call between the protagonist standing beside a locked gate and an out-of-touch state-government representative at her computer. Closed captions mediate the exchange:

Good-day, state control over Indigenous lands. Can I help you?

Somebody has locked the bloody gate here.

What? Look, I don’t know why somebody locked the gate. Yes you have to have the paperwork filled out...You have to have an anthropologist go over your claim...

Ah, true, I have to ask those people to go to my own country?

Look, it's the law.

My own country?

Well how am I supposed to know it’s your own country?

In acknowledgment of country and ‘āina—resilient ancestral places across the Pacific—HT22 brings together a number of the collective’s urgently needed films. Presented in a blackbox environment within Bishop Museum, an institution riddled with its own settler-colonial histories and overflowing with an abundance of unrealized Indigenous futures, the group's work helps to affirm connections between the vital and imaginative efforts of Indigenous communities near and far, in Australia and Hawaiʻi.

Karrabing Film Collective, Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (still), 2018, HD video, color, sound, 26 mins, 29 secs. Courtesy of the artists. © Karrabing Film Collective.

Karrabing Film Collective is based in Australia’ s Northern Territories and is an Indigenous media group whose work exists in a distinctive space between artists’ film, activism, narrative cinema and grassroots self-representation. Consisting of approximately 30 members—predominantly living in the Belyuen community—the collective approaches filmmaking as a form of critical resistance and self-organization. Australia’ s Northwest Territory government’ s Emergency Response intervention led to measures that have enabled police to enter Indigenous homes at will, drastically increased Indigenous incarceration for minor offenses, lead to cuts in social welfare and pressured clans to open their land to mining corporations. These issues, among others, come intoKarrabing’ s films, appearing through a method the group calls “improvisational realism” that creates a space both between and beyond documentary and fiction. Karrabing means “tide out” in the Emmiyengal language and refers to the northwest coastline of Australia that connects the members of the collective.

The Karrabing Film Collective uses film to analyze contemporary settler colonialism and through these depictions challenge its grip. In the shadow of Third Cinema and Theater of the Oppressed, Karrabing is creating a new model for Indigenous filmmaking and activism.

Karrabing Film Collective

Cameron Bianamu, Gavin Bianamu, Ricky Bianamu, Sheree Bianamu, Telish Bianamu, Trevor Bianamu, Danielle Bigfoot, Kelvin Bigfoot, Rex Edmunds, Claudette Gordon, Ryan Gordon, Claude Holtze, Ethan Jorrock, Marcus Jorrock, Melissa Jorrock, Reggie Jorrock, Patsy Anne Jorrock, Daryl Lane, Lorraine Lane, Robyn Lane, Angelina Lewis, Cecilia Lewis, Katrina Lewis, Marcia Lewis, Natasha Lewis, Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Quentin Shields, Aiden Sing, Kieran Sing, Shannon Sing, Rex Sing, Daphne Yarrowin, Linda Yarrowin, and Sandra Yarrowin.

In Memory, Roger Yarrowin and Alice Wainbirri.